Regardless of your level of legal training, we’re all guilty of ignoring the fine print but insurance coverage is often determined by the placement of an unnoticed word or punctuation mark in the language of the policy. Under Louisiana law, the insured bears the burden of proving that an incident falls within the terms of the policy. In contrast, an insurer seeking to avoid coverage through a motion for summary judgment bears the burden of proving that a provision or exclusion precludes coverage. Courts treat insurance policies like other contracts and therefore strive to interpret each term according to its true meaning. As straightforward as it sounds, a contract’s true meaning is always disputed even if on its face the language appears clear. This requires courts to hear creative arguments on the meaning of particular terms buried in the policy.

On June 8, 2010, in an unfortunate incident at the Library Lounge in Monroe, McKenzie A. Hudson (Mr. Hudson) was approached by an intoxicated patron and struck in the head. In December 2010, Mr. Hudson died from severe brain injuries allegedly suffered during the attack. Mr. Hudson’s mother filed a wrongful death/survival suit against several defendants including the entity that owned the bar as well as its principals. Several weeks later Ms. Hudson added First Financial Insurance Company (FFIC), insurer of the bar.

Recognizing the language of the bar’s insurance policy, Ms. Hudson admitted that her son’s assailant did not intend or expect her son’s death but instead it resulted when he lost consciousness, fell to the pavement, and fractured his skull. The particular provision at issue in the policy read that it did not provide coverage for assault, battery, or other physical altercation. The policy defined assault in part as “a willful attempt or threat to inflict injury upon another” and battery as “wrongful physical contact with a person without his or her consent that entails some injury or offensive touching.”

Ms. Hudson differentiated between the FFIC’s old policy language which was ambiguous as to “extraordinary” injuries and its current policy which included amendments intended to broaden and clarify exclusions. Ms. Hudson specifically pointed to the removal of an “or” between the assault and battery provisions which had the effect of causing the provisions to be read together. This eliminated coverage for all “intended” or “expected” injuries. Since her son was not intentionally killed or expected to die she argued coverage should be provided. In response, FFIC submitted numerous cases where similar assault and battery exclusions were upheld.

Like the trial court, the court of appeals granted summary judgment in favor of FFIC for several reasons. First, the court reviewed the cases submitted by the FFIC and concluded that the “overwhelming” majority of insurers were dismissed from suits arising from injury or death after an assault or battery. Furthermore, the court pointed to a similar case where it was determined that the presence of an “and” or “or” did not necessarily indicate that the provisions should or should not be read together. The court concluded that the provisions were clear in their language and that there was no question Mr. Hudson was the victim of battery. Therefore, the policy excluded insurance coverage for his death.

Although the courts demonstrate a reluctance to rule against the insurance companies in policy exclusion cases this does not mean a particular result is guaranteed. The terms of each insurance policy varies and requires careful review of its language before any legal action is taken.

Continue reading

Have you ever witnessed an accident? The experience can be overwhelming, leaving lasting, often overlooked emotional scars. Such consequences raise an essential question; can a witness to an accident seek damages in court? The subsequent lawsuit helps answer that question. The journey of the litigants through the intricate legal landscape reveals their unwavering determination to find solace for the emotional anguish they endured as witnesses to the tragic events.

Have you ever witnessed an accident? The experience can be overwhelming, leaving lasting, often overlooked emotional scars. Such consequences raise an essential question; can a witness to an accident seek damages in court? The subsequent lawsuit helps answer that question. The journey of the litigants through the intricate legal landscape reveals their unwavering determination to find solace for the emotional anguish they endured as witnesses to the tragic events. Insurance Dispute Lawyer Blog

Insurance Dispute Lawyer Blog

Insurance claims can be tricky, especially when multiple parties and contracts are involved. What happens, for example, when one insurance company claims they are not responsible for payment after a catastrophic event resulting in lost lives? The following Terrebonne Parish case follows this exact scenario.

Insurance claims can be tricky, especially when multiple parties and contracts are involved. What happens, for example, when one insurance company claims they are not responsible for payment after a catastrophic event resulting in lost lives? The following Terrebonne Parish case follows this exact scenario.  Allocating damages in a wrongful death case is challenging because putting a price on a life is hard. Therefore, if a family in a wrongful death case feels the jury abused its discretion in calculating that monetary value, then the family can resort to a motion for JNOV to try and correct the decision. However, this is a rigorous standard, and a recent case out of Baton Rouge outlines how a court reviews these motions.

Allocating damages in a wrongful death case is challenging because putting a price on a life is hard. Therefore, if a family in a wrongful death case feels the jury abused its discretion in calculating that monetary value, then the family can resort to a motion for JNOV to try and correct the decision. However, this is a rigorous standard, and a recent case out of Baton Rouge outlines how a court reviews these motions.  Medical malpractice claims are brought when a patient is a victim of negligence at the hands of their physician. Due to the nature of this category of claims, stories of medical malpractice are often horror stories showcasing worst-case scenarios. Even further, the most intense medical malpractice claims result in the death of the patient. Understandably, the patient’s family may seek to find responsibility for the death of their loved one. In the following lawsuit, a family fails to show the legal requirements to bring a medical malpractice claim after their family member died during surgery.

Medical malpractice claims are brought when a patient is a victim of negligence at the hands of their physician. Due to the nature of this category of claims, stories of medical malpractice are often horror stories showcasing worst-case scenarios. Even further, the most intense medical malpractice claims result in the death of the patient. Understandably, the patient’s family may seek to find responsibility for the death of their loved one. In the following lawsuit, a family fails to show the legal requirements to bring a medical malpractice claim after their family member died during surgery.  We have all read headlines about lawsuits filed against gas and energy companies by workers who have developed health problems at their facilities. But what happens when a plaintiff files a lawsuit which could be barred by a workers’ compensation act? Will the claim be able to withstand a peremptory exception? How does the plaintiff fight against such a motion?

We have all read headlines about lawsuits filed against gas and energy companies by workers who have developed health problems at their facilities. But what happens when a plaintiff files a lawsuit which could be barred by a workers’ compensation act? Will the claim be able to withstand a peremptory exception? How does the plaintiff fight against such a motion? Imagine being on a jury – everything you hear has gone through a process of admittance to be used as evidence during the trial. What the jury is told often plays a role in what the jury thinks of the parties and how it assigns blame amongst them. The following lawsuit explores what happens when a defendant challenges the admittance of a piece of evidence it believes unfairly swayed the jury against it. It also helps answer the question; can a litigant exclude evidence in a car accident lawsuit?

Imagine being on a jury – everything you hear has gone through a process of admittance to be used as evidence during the trial. What the jury is told often plays a role in what the jury thinks of the parties and how it assigns blame amongst them. The following lawsuit explores what happens when a defendant challenges the admittance of a piece of evidence it believes unfairly swayed the jury against it. It also helps answer the question; can a litigant exclude evidence in a car accident lawsuit? People rely on public services daily, from fire departments to police officers. But what happens if a public entity is responsible for an injury? Can they be held liable for negligence? A recent case out of Grand Isle, Louisiana, shows how public entities can be shielded from liability for negligent conduct in some circumstances. It also helps answer the question; Can a state fire marshall be liable for inspector negligence in a wrongful death lawsuit in Louisiana?

People rely on public services daily, from fire departments to police officers. But what happens if a public entity is responsible for an injury? Can they be held liable for negligence? A recent case out of Grand Isle, Louisiana, shows how public entities can be shielded from liability for negligent conduct in some circumstances. It also helps answer the question; Can a state fire marshall be liable for inspector negligence in a wrongful death lawsuit in Louisiana? Driving poses undeniable risks. However, travelers may need to consider how unsafe a barrier curb may be in certain situations. When is the state liable for these conditions? A case from the St. John Baptist parish considered how the state department of development and transportation was at fault for construction risks that contributed to an accident.

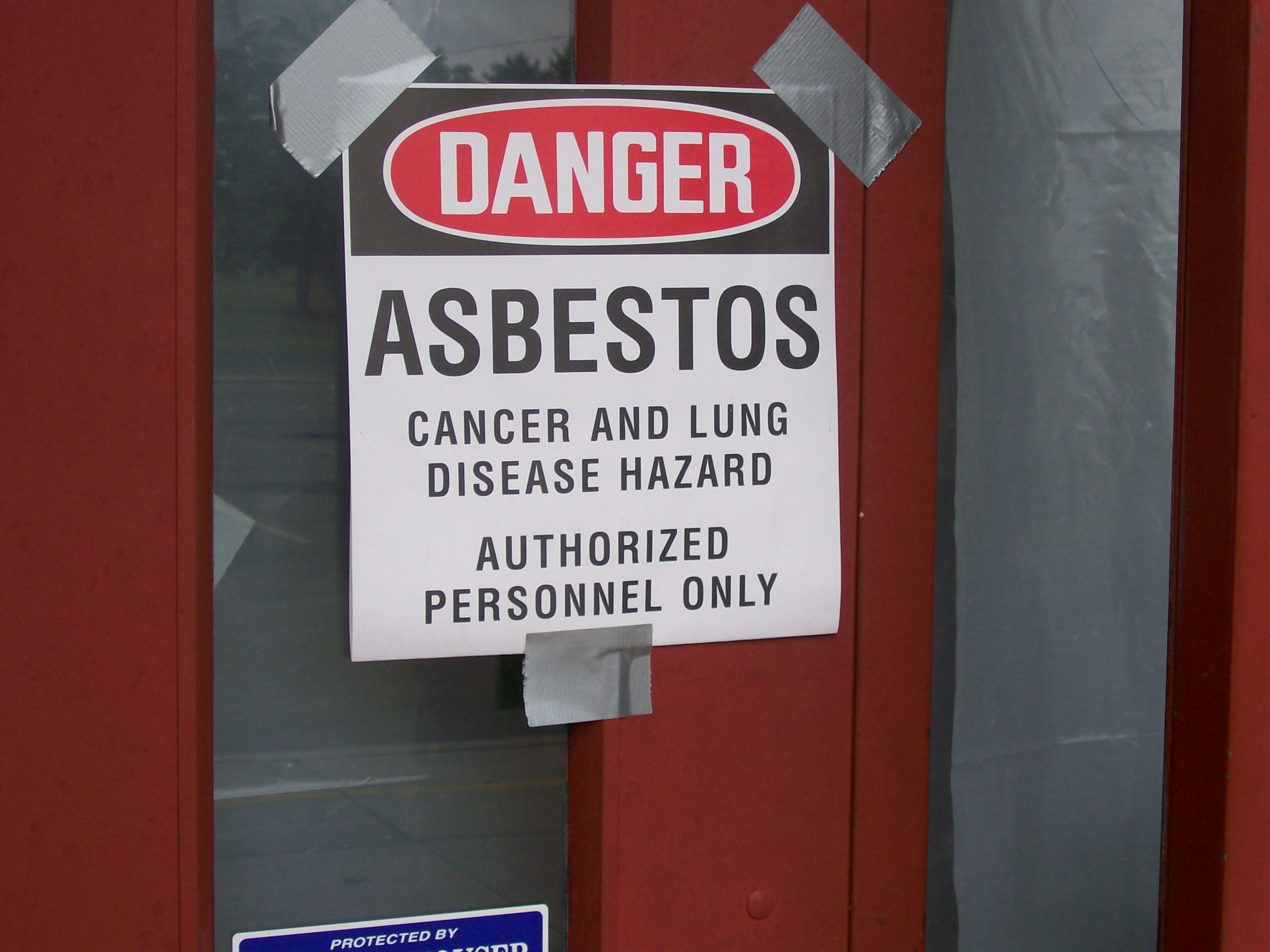

Driving poses undeniable risks. However, travelers may need to consider how unsafe a barrier curb may be in certain situations. When is the state liable for these conditions? A case from the St. John Baptist parish considered how the state department of development and transportation was at fault for construction risks that contributed to an accident.  Risks are involved with many jobs. While employees may take risks at work, knowingly or unknowingly, one does not usually expect to put their family at risk while on the job. Jimmy Williams Sr found himself in this situation when his exposure to asbestos at work impacted his wife’s health through her handling his work clothes.

Risks are involved with many jobs. While employees may take risks at work, knowingly or unknowingly, one does not usually expect to put their family at risk while on the job. Jimmy Williams Sr found himself in this situation when his exposure to asbestos at work impacted his wife’s health through her handling his work clothes.